“This methodology helps designers navigate the very difficult task of involving every stakeholder and ensures that solutions are created that meet all of their needs”

Minke Dijkstra

A common myth that many believe is that great innovations arrive unexpected or unplanned, like a flash of lightning striking only those with highly creative minds. We might find ourselves using words like ‘talent’ or ‘genius’ to quickly explain what we cannot understand or to contextualise this phenomenon that can be difficult to reproduce. However the truth is, coming up with ground-breaking innovations may not be as unattainable or mysterious as we think.

The difference between a good designer and great designer is how they look at problems. Good designers can look at a problem from one point of view and come up with a range of solutions. Great designers can look at a problem and uncover transformational moments of clarity that can change the way we see and interact with the world. How do they do this?

Many leaders in the field of Design and Innovation have laboured over this question in an attempt to better understand the creative process. What they have found is that all great designers have an extraordinary ability to understand and translate ‘deep customer insights’. But what does this actually mean?

Using Deep Customer Insights to Innovate

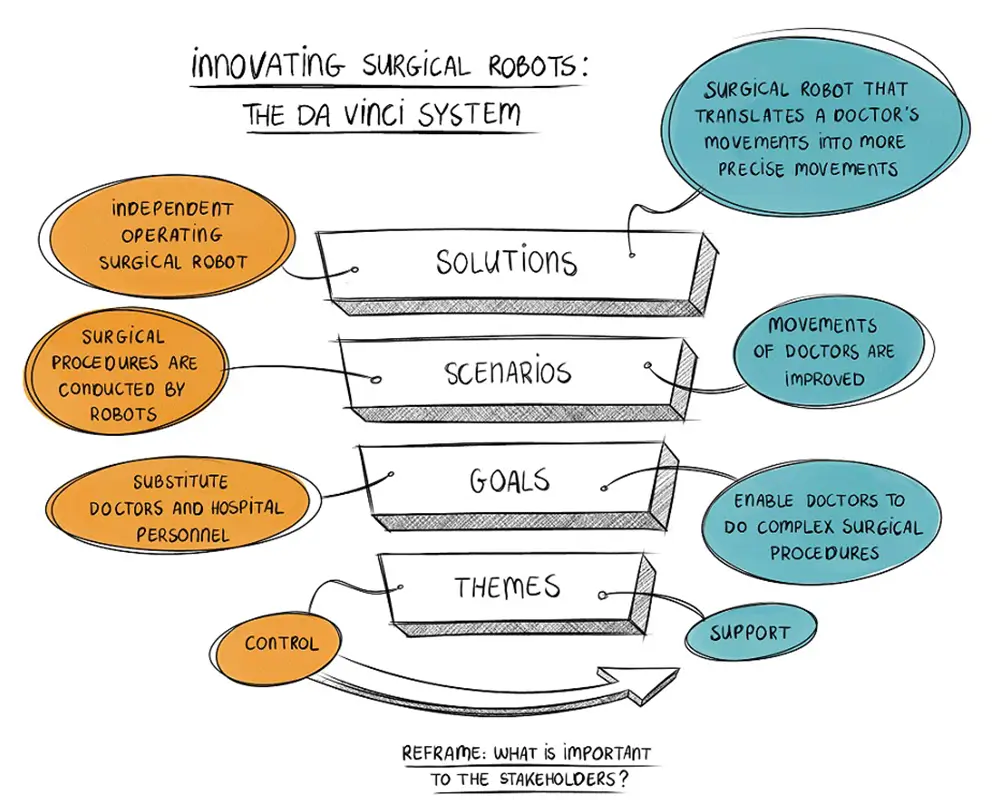

Mieke van der Bijl-Brouwer and Kees Dorst from the Design Innovation Research Centre at the University of Technology Sydney have been working on unpacking this question through an analysis of what ‘deep customer insight’ means in the context of design and innovation. Key findings from their research suggest that there are four levels of human insights – Solutions (what), Scenarios (how), Goals (why) and Themes (why). They have since gone one step further and integrated these findings into a four-layer model of insights into human needs and aspirations for design and innovation.

Interestingly, what they have found is that during the creative process when exploring the deepest level of this model, the Thematic Level, innovations begin to sprout and grow. To explain how this happens, let’s take a look at the creative process of how a team of product developers invented ‘The Da Vinci System’, a ground-breaking surgical robot that translates a doctor’s movements into more precise movements, using the four layer model.

The medical industry is constantly on the hunt to find new and better ways to reduce risk and human error. Prior to the invention of The Da Vinci System, many believed that the best way to do this was to replace doctors and hospital personnel with independent operating surgical robots.

However, when the team of product developers investigated the Thematic Level by looking deep into what really mattered to doctors and hospital personnel, they found that they didn’t want to be replaced or controlled; in fact what they wanted was support in highly complex situations. By identifying ‘Support’ as the underlying theme, the team were able to look for the best solutions in a frame of mind that matched the core needs and aspirations of the users.

This process of changing perspectives is what Donald Schön defines as ‘Reframing’. However to explain how the team successfully translated an abstract concept like ‘support’ into an entirely new product, we need to take a closer look at the influence of ‘Themes’ throughout the creative process.

The Importance of Using Themes to Reframe

Kees Dorst’s research has found that Frames and Themes are interrelated. Themes are considered to be the deepest level of insight into human needs and aspirations, which means they can appear in any context and across any setting. Themes are universal. While this may seem like a daunting proposition, similar to looking at a road sign of infinite possibilities along the creative journey, this is precisely what makes Themes so powerful if used the right way. To understand how Themes can be used to reframe, let’s take a look at the Theme ‘support’. Think about all of times you experience support during your day to day activities. What does ‘support’ mean to you? When we study Themes outside of their original context, we get a better understanding of what the Theme means to different groups of people and entirely new frames of thought can arise. This is what enables innovative ideas to grow.

IDE’s New Approach

Together with the Design Innovation Research Centre, Minke and ide identified a need to translate the abstract skills of theme creation and reframing with the four-layer model into one streamlined practical methodology. This methodology is called ‘Thematic Framing’.

Thematic Framing works by providing a structure that aligns stakeholder interests, needs and aspirations, helping foster opportunities for reframing and theme creation to occur. This methodology also helps lessen the tug-o-war between competing stakeholder interests by establishing a common ground so that the best possible solutions can be found. “Many designers are already able to innovate” Minke says, “but this methodology helps designers navigate the very difficult task of involving every stakeholder and ensures that solutions are created that meet all of their needs”.

For many product developers, balancing the need to innovate at lightning fast speeds with the often meticulous and time consuming task of deeply understanding a problem, will always present a challenge. However, what we have found is that by using Thematic Reframing, we may in fact speed up the innovation process and produce much better results.

Do you have a question or a comment you would like to share? Visit our ide Connect community to join the discussion.

Further readings: Bijl-Brouwer, van der, M., & Dorst, K. (2014). How Deep is Deep? A Four-Layer Model of Insights into Human Needs for Design Innovation. Proceedings of the Colors of Care: The 9th International Conference on Design & Emotion, 280-287. Bogotá, Colombia: Ediciones Uniandes. Dorst, K. (2015). Frame Innovation: Create New Thinking by Design. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press.